The years spanning 1878-1883 were quite possibly the most important in Bismarck’s history, cementing Bismarck’s future as a regional center for government, healthcare, and commerce covering hundreds of miles. It will become capital of Dakota Territory and host the territory’s first hospital.

Mandan Founded; Railroad Construction Resumes

After surviving bankruptcy, Northern Pacific emerged with enough capital to complete its northern transcontinental railroad.

Beginning in 1878, roughly five years after construction abruptly halted, Northern Pacific resumed construction activity and established a work camp on the west side of the Missouri River. By December, the site was chosen as the new county seat for Morton County and christened “Mandan,” named for the Native American Tribe who once occupied the land. Apparently, several other names were in consideration, including simply Morton. Evidently, there was another small confrontation in the town’s name, in which a local postmaster attempted to name the town after himself.

The former courthouse in Lincoln township, the civilian camp located just north Fort Abraham Lincoln that was formerly the Morton County Seat, was set aside to be a school.

In February 1879, General Rosser employed about fifty men to lay down temporary track across “Nature’s ice bridge” – the frozen river, connecting Bismarck and Mandan for the first time. Its primary purpose was to transport supplies for the railroad. By the time of its discontinuation on March 11th, 538 carloads of material had been transported across the river.

By this time, track was laid to about five miles west of the Missouri River, almost to the Heart River, and efforts were well underway to recruit around five hundred men for grading the westward line and bridge construction. General laborers were paid $1.25-$1.50 per day and bridge contractors starting around $3.00 per day.

Less than a year since its formation, Mandan’s population was already estimated at 230 – nearly all railroad workers, and was rapidly increasing.

P.J. Callahan’s “Mandan House” was likely the first business within city limits; a 24×56-foot motel and restaurant for the railworkers that was already operating. The first framed building erected in present-day Mandan was a two-story office for the chief engineer.

Lots were first put up for sale and legally transferable in March, by which time 150 lots were already reserved and permits for forty buildings approved. Pat Byrne’s restaurant may have been the first private building permit.

In April, the official plat was filed and a townsite organization established. Edmund Hackett – Bismarck’s first appointed mayor, was elected president of the Association.

That same month saw the first baby born in Mandan, to Mr. and Mrs. Milan Harmon.

The Mandan Criterion, the city’s first official newspaper, published its first edition on May 24th. It remained Morton County’s official newspaper until the Mandan Pioneer was selected for this honor in January 1882 – three months after its first edition.

1880-1882: River Bridge Completed

By 1880, Bismarck’s population was nearing 2,000 and it had established a strong foundation to support a prosperous city. With the gold rush ended and little progress in completing the railroad, Bismarck saw little change for the first two years of the decade.

One major development was the opening of a long-time lodging establishment. The Pacific Hotel – later Grand Pacific Hotel – first opens in 1880 and remains operating until 1974.

The contract was let in January 1881 to complete the multi-million dollar “great iron bridge” spanning the Missouri River. It finally opened in October 1882, nearly ten years after the railroad first reached Bismarck. While the ceremonial golden spike took place the month prior, in western Montana, the bridge effectively completed the line.

To this day, the original granite piers, quarried at Sauk Rapids, Minnesota, still support the structure, but the spans and deck were replaced in 1905 to handle heavier loads.

Construction commenced in June for the Bismarck National Bank building at a cost of $35,000. It will be the city’s largest private building upon completion. The bank, still operating today, re-branded as BNC National Bank in 1995 upon acquiring Metropolitan Federal Bank from Minneapolis-based First Bank System Inc.

The following year, 1883, marked two significant progressions: Establishing the territorial penitentiary in Bismarck and, more importantly, moving the capital of Dakota Territory from Yankton to Bismarck.

Despite its seemingly obvious choice as capital, however, Bismarck was not initially favored among the dozen or so prospects, and Yankton would not willingly cede the capital without a fight.

Capital Commission Bill

In March 1883, the territorial legislature narrowly passed the capital commission bill that demoted Yankton as capital of Dakota Territory and established requirements for selecting a new capital. Governor Ordway signed the bill, known as house file number 217, on March 8th.

Commissioners

The bill defined the nine-man commission tasked with selecting the capital, setting a July 1st deadline. It proclaimed that the commissioners be paid $6 per day for their work and that each enter into bonds totaling $40,000.

Two of these commissioners ultimately become among Bismarck’s most notable historical figures. One was Alexander McKenzie, a Northern Pacific agent and lawman from Bismarck who later becomes a powerful local political boss. Another, the committee chairman, was General Alexander Hughes of Elk Point, who later establishes Hughes Electric with his son in Bismarck and becomes a principle real estate investor.

Requirements

The commission bill required that the chosen city donate or guarantee $100,000 and 160 acres of land to house a capitol for the seat of government. Another requirement was that the site be central and accessible from all portions of the territory. Commissioners considered both the current and future boundaries, given that there was contemplation that the territory would be split at the 46th parallel (ultimately, it was the 49th parallel).

Selecting the Capital

At least nine cities were under legitimate consideration to be the new capital. Huron, Mitchell, Pierre, Ordway, Frankfort, and Steele were the first to submit bids, followed by Bismarck, Aberdeen, Redfield, and a handful of others.

Statistically, Bismarck was a logical choice. Its location was roughly 40 miles from the territory’s geographic center and would have remained within 50 miles after the foreseeable boundary split. It was also positioned at the crossroad of the northern transcontinental railroad and Missouri River, the highways of the era. Furthermore, the Northern Pacific Railway – and all its clout – favored Bismarck.

In reality, Bismarck was perceived to be on the border of civilization and some viewed the area west of the Missouri River as barren waste. By his own admission in an interview with the St. Paul Dispatch, Chairman Hughes’s perception later improved after traveling the region during the vetting process.

With the bulk of the population centered in the southern half of Dakota Territory, it was anticipated that the capital would remain there. In particular, Huron and Redfield were thought to be early front-runners.

As an underdog, Bismarck presented a competitive bid that far exceeded the minimum requirements: 320 acres, along with the monetary stipulation. 160 of those acres would be sold and guaranteed by private citizens for $300,000, bringing Bismarck’s total offer to $400,000 and 160 acres of land. Northern Pacific would donate the land while private citizens would contribute the remaining funds.

The commissioners visited each city under consideration before convening in Fargo in May to make the final determination.

There, in a last-ditch effort, a group of Fargo citizens demanded a hearing in front of the commission to request a delay, in an attempt to persuade Fargo as a contender. Fargo never was a serious contender, though. The bill’s stipulations required that the capital be centrally located within the territory. After a short hearing, the request was denied and the first ballots were cast on June 1st.

Only one commissioner initially voted for Bismarck… Alexander McKenzie, Burleigh Country Sheriff and an agent for Northern Pacific. Interestingly, McKenzie himself voted against Bismarck in the second ballot round, opting instead for nearby Steele.

After 13 votes over two days, Bismarck won the majority on June 2nd. McKenzie is credited with negotiating to procure enough votes. In the end, Hughes cast the tie-breaking vote after previously supporting Mitchell and Redfield.

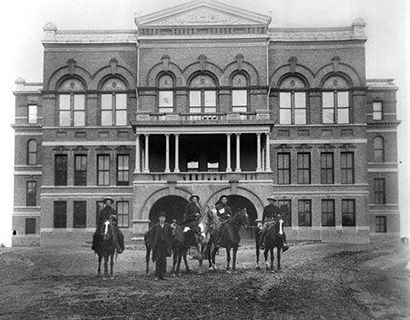

Original Capitol’s cornerstone ceremony. Numerous dignitaries attended, including Sitting Bull and former President Ulysses S. Grant.

Source:

State Historical Society of North Dakota (C0865)

Upon approval by the governor, Yankton was immediately stripped of its position. Territorial offices were established in a temporary capitol in Bismarck until a permanent structure could be completed. The cornerstone for a new capitol building was laid on September 5. Numerous dignitaries attended, including Sitting Bull and former President Ulysses S. Grant. First occupancy of the new capitol occurred at the end of 1884, just in time for the 1885 legislative assembly.

Legal Challenge

Yankton would not surrender its capital easily and challenged the constitutionality of its relocation. Allegedly, only the legislature and governor could assign a capital, not a commission. District Chief Justice Edgerton, a Yankton local, agreed. He granted a restraining order against the commissioners, declared that its officers were appointed illegally, and removed them from office.

The legal matter was appealed to the territorial Supreme Court, who overruled Judge Edgerton’s decision, but not until September 1884, when construction was already nearly complete on the new capitol. Nevertheless, Bismarck was legally victorious in procuring the capital.

Other 1883 Developments

Also in 1883, the Dakota Block, also known as the Flannery Block, is completed that October. The Gothic-style building on the northeast corner of 2nd Street and Main Avenue is Bismarck’s second-oldest surviving building.

Several other significant construction projects that year included the First National Bank building for $65,000, the territorial prison for $50,000, the North Ward School for $30,000, and the Merchants National bank for $27,000.

More Chapters

Next Chapter:

1884-1929: Industry, Fire, and Rebirth